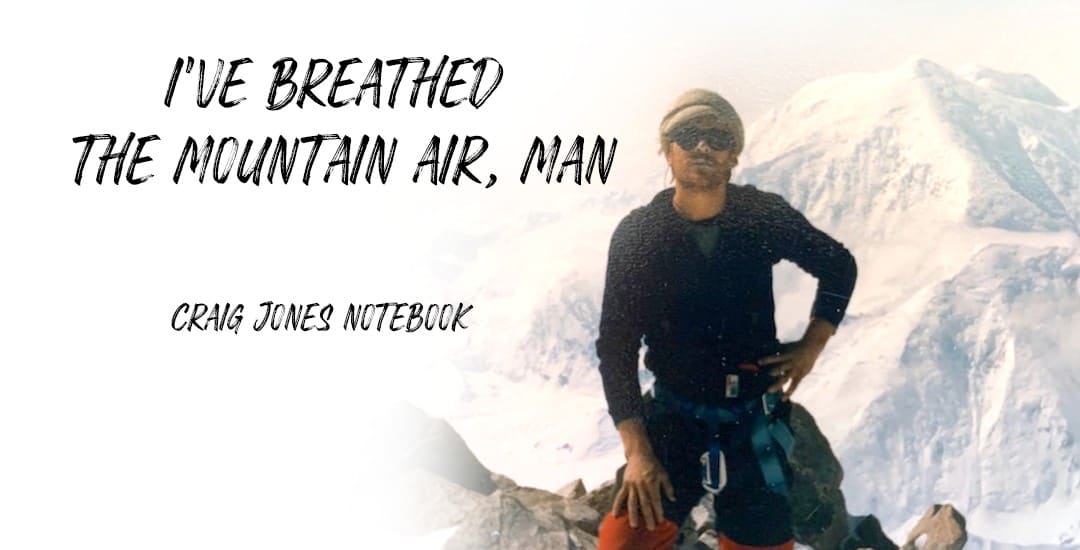

Craig Jones Columnist

Thirty five years ago this past May I was making notes in a journal, writing in a high cold hand in a high cold book with high cold thoughts.

Friday, May 2, 1986, I wrote–

“Pulse, daily.

I like the lunches–sardines, canned oysters, cheese blocks, rye crisp, e.g. bagged for daily calories

1st BM at Kahiltna Throne. Plane came in (while I was on said throne), I remained non-plussed.

Germans (or Swiss, not sure) camped near us on the glacier. Is Kahiltna polyglot?

The peak has remained in view since our arrival. Tonight, has disappeared. Snow beginning.”

Nothing particularly lyrical, nothing very interesting, just black and white and earthy observations.

We were to take our pulse daily and make note of any significant changes.

The lunches I said I liked were designed to be lightweight, easily-accessible and belly-filling.

The throne upon which I was non-plussed was an open air, al fresco wooden shitter on the Kahiltna glacier.

There were all kinds of languages spoken there.

There was a lot of snow, all the time.

I was on day two of a climb up Denali, once called Mt McKinley, the tallest mountain in North America, and I was trying to find my voice and my way of being on the mountain. I just scribbled down whatever seemed important at the time.

It was all in front of us, at one point, and now it’s 35 years in my rear view. I have written a lot about the mountain, for it has cast a long shadow.

By the end, three weeks later, I had gotten to the idea that no one in the history of mountaineering had ever gone up Denali the way I did. Now, I am no one’s elite climber and I will never pioneer a first route. I had to come face to face with that early on.

I still laced crampons on my boots the same way and set my face to the big wind and watched the same cobra-colored climbing rope runnelling through the glacier and was just as vulnerable to HACE (high-altitude cerebral edema, AKA mountain sickness). I did all these in the same way as the elites.

I knew, though, beyond any doubt, that I had climbed in my own way, with my own thoughts and my own experience. I had climbed my own Denali. That’s what I called it – “My Own Denali.”

The truth is that everyone has their own Denali and their own story. We all do. It is our task of tasks to fall in love with our story and be grateful for it. It is not always easy, no question. I don’t love my whole story yet, but I want to. I love more of it day by day, because I am the author, and I get to choose.

I continued in my journal–

“Words seem to fail. Why does an exuberant ‘What a day!’ or ‘That’s spectacular!’ answered with ‘Oh, man!’ seem so trite somehow up here?

Why do we say words fail or are inadequate anyway? Is it because they can’t actually replace first-hand experience, the reality? No, words can’t replace first-hand, but don’t say they fail. Just accept their limitations, like with photos.”

All these years later, I’m still trying to frame it and say it and own it and it’s great work, really. It was overpowering, the magnificence of Denali, and most of what I experienced has just become part of me and for me alone, though on some occasions I’ve been able to convey some of it to others.

What I was really saying at the time, though I didn’t know it, was that it’s about our inability to use words rightly in those moments. There is a multitude of right words and, for those who would write, there’s the constant thrill, mixed with anguish, of finding them. Even Peter Matthiessen, who seems to have been able to write anything, asked who had the words “for such ringing splendor,” in The Snow Leopard. It’s the writer’s burden, and joy, I figure, to have at it anyway.

And so I wrote on–

“May 12, 1986 (33rd birthday today)

At 14-3 (14,300′), my pulse is 88. Two pee bottles used last night (no one gets up to piss after the night wind wakes up like a hungry beast) and the temp hit -28. We had climbed up from 11K, with a stop at our 12-6 cache, to this elevation (14-3). Hard climb and I have the beginnings of a blister on my heel. Here it is actually crevasse-free and less claustrophobic as we can walk around untethered (unroped, that is, to a fellow climber). Medical camp to come in today with choppers and Army experimental subjects (were they voluntold? Welcome to the Army, dude.) to test an altitude sickness drug (dexamethasone, I believe). Some soldiers will get that and some will get placebos.Steve (one of our Canadians) is apparently having some altitude problems himself. With morning warmth, frost inside our tents starts to melt and snows on us. Mark jokes about a major meltdown unless we get moving. There’s more talk of pulses (which we check daily) and pee bottles. Larry may even press a water bottle into service. They all sang ‘Happy Birthday’ to me and Ralph had a snow block with a lighter in it to serve as an ersatz cake.

The crevasses are menacing as we stare into the black depths. We count our steps and we sound like gulls as our ice axes squawk in the still air and the crampon extenders leave tracks that evoke fossilized vertebrae. The terrain changes and I shift the ice axe to my left side. Snot runs freely and freezes in my mustache and beard. I see a shit bag wedged in a crevasse. That and being on the rope behind slower climbers, stopping and starting, takes a lot of the romance out of climbing. It fell on me to help cook supper and I lost patience with one of the stoves which was hard to pressurize. We carry half rolls of toilet paper to help conserve weight.

All in all, a memorable birthday, the highest and coldest yet.”

There’s a lot more to this journal, and the lessons still keep coming, all these years later.

I never made the summit, because I chose to stay with my friend at the high camp. He had come down with HACE, which I alluded to earlier.

“A baffling ailment,” Jon Krakauer writes in Into Thin Air, “HACE occurs when fluid leaks from oxygen-starved cerebral blood vessels, causing severe swelling of the brain, and it can strike with little or no warning. As pressure builds inside the skull, motor and mental skills deteriorate with alarming speed—typically within a few hours or less—and often without the victim even noticing the change. The next step is coma, and then, unless the afflicted party is quickly evacuated to lower altitude, death.”

My friend couldn’t even take the field sobriety test. He’d take three steps and fall over.

Whenever the climb has come up, since then, he has referred to it as “the ultimate act of friendship.” Recently, my wife and I were having what we thought at the time was a post-COVID dinner at their place in Boston’s South End. Denali came up naturally and he said, “It was my fault.” He and his wife are both in their eighties and he is dealing with some cognitive loss, but I finally got to say to him with witnesses around (because I had been thinking about what to say if it came up again) that I have never regretted, not for one second, not summiting.

I said, first of all, I wouldn’t have been on the mountain without you. It was your idea in the first place, because your sister lived in Talkeetna. Secondly, I probably wouldn’t have done all these years of winter climbing in the White Mountains were it not for you. At least, there would had to have been some other narrative.

Thirdly, I learned first-hand and for real, that the journey is what’s important, not the destination. I mean, sure, you go to a place like these Alaska mountains with a goal in mind. You don’t just fly to Anchorage and pack all this shit up there and wander around aimlessly. You intend to stand on the top.

But you stand on a summit for a very few minutes, maybe take a photo or two, then start the down-climb. You get to say, yeah, I did that. But, most of the time is spent on the journey. That’s where the richness is. That was driven in deep, as deep as the cold in our bones, as deep as the crampons biting the snow, as deep as the yawning crevasses. You can’t buy a lesson like that.

I learned that relationships can be inconvenient. I went to Alaska to climb with my friend and bagging the peak wasn’t in the same universe as that.

I climbed My Own Denali, in a way no mountain has ever been climbed. And that learning was part of it. There are a lot more Denalis out there, before I take my last breath.

Johnny Cash sang

I’ve been everywhere, man.

I’ve been everywhere, man.

Crossed the deserts bare, man.

I’ve breathed the mountain air, man.

Of travel I’ve had my share, man.

I’ve been everywhere.

I have breathed the mountain air, man, and like the Stranger said in The Big Lebowski, “I can die without feeling like the good Lord gypped me.”

Great story, I thank you as my journey continues….. if feels great!!