By Dr. Paul Nathanson

Special Guest Contributor

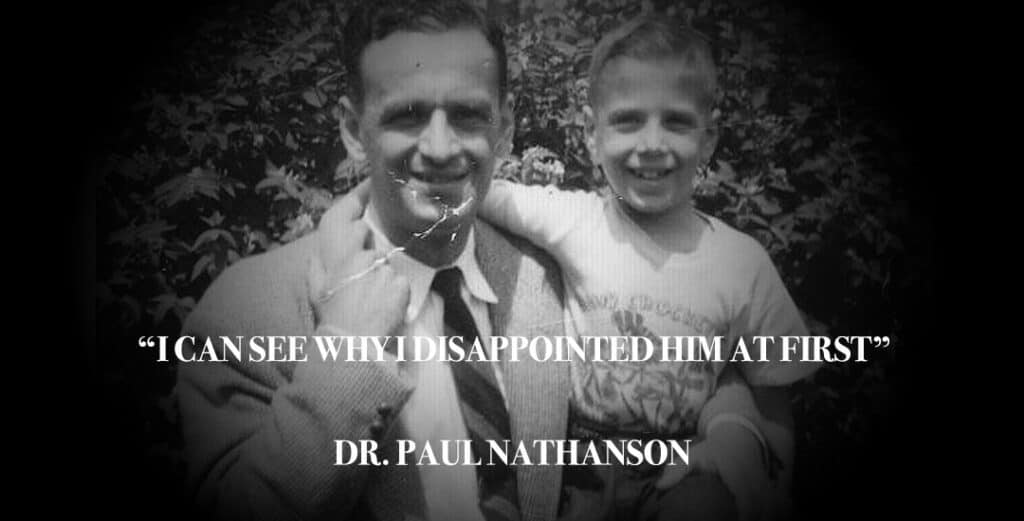

My father, who died 15 years ago, had a difficult but close and even intense relationship with me.

From my perspective as a boy and young man, he seemed overly judgmental. I grew up thinking that I could never make the grade in his eyes, never be good enough to satisfy his lofty expectations of me or even to satisfy my own. And his standard for honorable manhood, which he applied to himself no less than to me, did seem unattainable.

One day, we were at a restaurant. Adding up the check in his head, as usual, he realized that the waiter had made a mistake. When he paid, Daddy paid the correct amount and announced that the written tab had been not too high but too low. I admired that even then.

I wasn’t so sure about his notion of manhood. It focused heavily on duty and sacrifice—not things that most people, certainly not children, are eager to embrace. Worse, perhaps, Daddy expected me to learn skills that didn’t interest me. He played with me and took me to museums, sure, but he also tried to help me with my arithmetic homework and was visibly exasperated, night after night, by my inability to understand what he considered common sense. Mummy understood me, because she couldn’t do math any better than I could. But, as I saw it being a woman, she didn’t have to do math. To be blunt, I usually preferred to be with Mummy, who gave me uncomplicated and unconditional love.

Daddy confessed, many years later, that I had disappointed him at first. And I can see why.

I was an outsider for several reasons in childhood. Apart from anything else, I was both unwilling and unable to absorb prevalent but superficial (and ultimately both destructive and self-destructive) notions of masculinity. In fact, I was gay. I had to invent myself, therefore, and I’m proud of my ability to do so. But it was Daddy who first taught me to be independent—that is, as I eventually understood, to think for myself but within a larger moral context. He taught me to become more fully human, in other words, not to embrace either conformity or “autonomy” (an overused and misused word these days).

Daddy lived long enough to see me become an effective member of society. As a child, I had disappointed him. I knew that and resented him for being disappointed.

As an adult, though, I see that expressing his disappointment was precisely the right thing for him to do, no matter how unpleasant it was for me. Hiding it, by contrast, would have been precisely the wrong thing to do, no matter how therapeutic for either of us at the time. And when he did say that he was proud of me, eventually, it really meant something.

One day, in the middle of some argument, he suddenly turned to me and said, “Paul, you’re a learned man.” OK, I was much too old by then for those words to give me a sense of self-confidence. But we both realized immediately that this was a moment of profound fulfillment; a father had symbolically conferred the symbolic mantle of manhood on his son. I never did learn arithmetic, but I had made him proud of me in other ways. This was my secular bar mitzvah.

On the other hand, Daddy still blamed himself for not pushing me hard enough to become more financially secure. We had time, fortunately, to talk about that. After spending many years doing research on manhood, including fatherhood, I told him that he had done exactly what every father needs to do. I didn’t have to add that he had done so not by consciously adopting the approach of this or that expert but by subconsciously absorbing the legacy of human experience after countless generations.

I believe that fathers and mothers are not interchangeable. (What a sad commentary it is that I should have to say what earlier generations would have considered self-evident.)

Mothers have historically given children unconditional love. “I’ll always love you, no matter what you do or don’t do.” Fathers have historically required their children to earn love—that is, the form of love that we usually call respect—in order to leave home and function effectively in the larger world. “I’ll respect you if you’re worthy of respect (which is a form of love). This means that fathers, unlike mothers, have seldom been able to measure their effectiveness adequately in terms of immediate emotional gratification. Spontaneous displays of affection from their children don’t necessarily mean, after all, that fathers are doing what’s best for them. Young children know very little, in any case, about what their fathers do for them behind the scenes. Moreover, they often resent having to meet expectations or endure constant testing. As for fathers themselves, they often find it hard to express love for their children directly for fear of sending a double message.

It requires a massive cultural effort to promote good parenting. For fathers, that means a whole lot more than merely bribing or threatening men into providing material resources for their families. In short, fathering is inherently more complicated, more ambiguous, and more perilous (though not more important) than mothering.

I’m dismayed, therefore, to find that our society seems hell-bent on undermining the culture of fatherhood and therefore of manhood as well. My research with Katherine Young, a Canadian religious studies professor at McGill University, indicates that misandry pervades our culture (though not to the exclusion of misogyny). Boys grow up learning, though not necessarily accepting, that every social problem is their fault. That alone prevents them from absorbing a healthy collective identity. Girls and women are good; boys and men are either evil or inadequate.

In addition, however, our research indicates every person and every group must, to have a healthy identity, be able to make at least one contribution to society that is (a) distinctive, (b) necessary, and (c) publicly valued. Now that women can take over two of the three historic functions of men, “provider” and “protector” (if necessary and even if possible, in both cases, with the state’s help), only “progenitor” remains. And to be a progenitor—that is, a father—in any meaningful sense is to care for children in the way that I’ve outlined here: not merely to contribute a teaspoonful of sperm or even a monthly check, not merely to be assistant mothers by changing diapers or going to school plays (let alone expressing unconditional love in order to reap immediate emotional gratification), but to perform the awkward task of requiring their children to earn respect from others. This is not the same as “discipline,” by the way, although self-discipline is indeed something that all children need.

If more fathers could do so, knowing that it can take years for children to respond with deep gratitude, they’d be helping not only children in general but also sons in particular. If we could find ways of honoring at least this onedistinctive and necessary contribution, after all, then boys would know that society needs them and even relies on them to become adult men. At the moment, boys know nothing of the kind. And many of them are reacting on the assumption that an unhealthy identity—one that countless pop cultural productions portray in connection with coarseness, vulgarity, ignorance, immaturity, drunkenness and even brutality—is better than no identity at all.

At best, in this age of heroic single mothers and sperm banks, the message to boys is that fathers are assistant mothers and therefore luxuries. Many divorced fathers find themselves reduced even further to the level of walking wallets. At worst, the message is that fathers are potential “deadbeats” or even child molesters and therefore liabilities. Boys now learn either directly or indirectly, therefore, that there will be no room for them as men in family life and that they will therefore have no moral stake as men in the future of society. If that isn’t an ominous sign, what is?

And yet, even now, most men do care for their children in this way. Congratulations, then, to all the confused and beleaguered fathers out there for continuing to do what is often a thankless job.

As for me, I like to think of myself as a father. After all, I had a fine example to follow. I never married and had children, so my children are my books and my former students.

And yes, I expect my family and friends to wish me a happy Father’s Day.

Paul Nathanson has a BA (art history), a BTh (Christian theology), an MLS (library service), an MA (Judaism and Islam) and a PhD (religious studies). He studies the surprisingly porous boundary between religion and secularity especially in popular culture and political ideologies. Over the years, he has fathered books. His first-born was “Over the Rainbow: The Wizard of Oz as a Secular Myth of America.” Younger children include four books on men in connection with the fallout from ideological forms of feminism: gynocentrism and misandry. He lives in Montreal with his teddy bears.