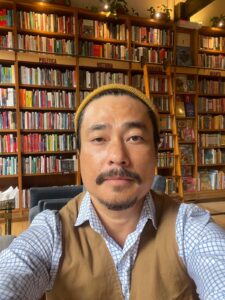

Khai Nguyen

Guest Writer

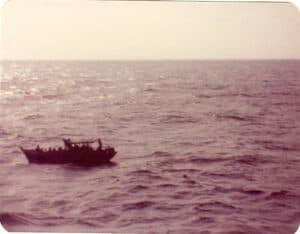

I left home the first time on a boat. It was a small boat my dad built with no sails and no motor: just oars. The waves, as my dad tells it, were at least 40 feet high from tip to trough. After five days and nights of paddling in the chop, having gone a very short distance, we were picked up by an American aircraft carrier group somewhere in the South China Sea off the coast of Vietnam.

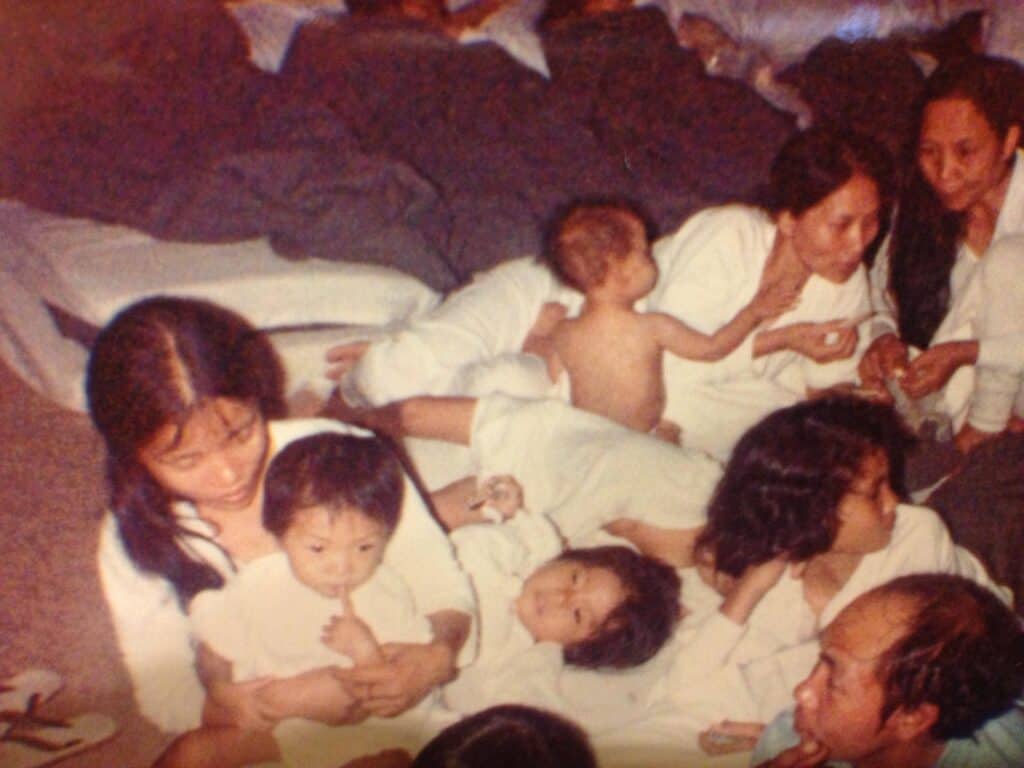

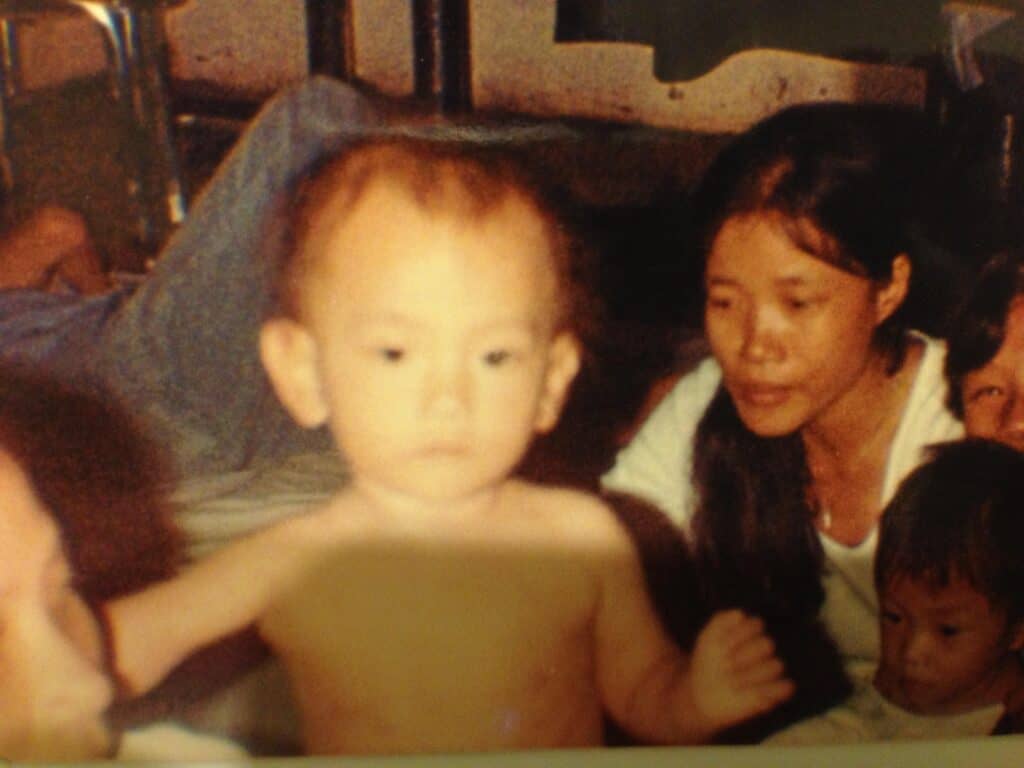

They pulled us from the sea and took us – my parents, my siblings, and I – to the Philippines. From there we were sent to Washington State, and were cared for by an American foster family who sponsored us. I don’t remember much of this: I was only an infant.

We lived in a rickety old house with thousands of rats in the basement – that I remember, and I also remember it as the only time all five of us siblings got along. My dad worked moving furniture while mom sewed clothes for just a few cents per garment. We ended up living with an aunt in Long Beach, California, all seven of us in her living room. It was really uncomfortable, as was the rest of the east Long Beach ghetto.

Eventually, my dad finished school, got his real estate license, and we got a better house. I got straight-As for a while, and headed off to middle school. My parents, whose Catholicism didn’t endear them to the North Vietnamese victors, had always gone to church; but as they got older they became more and more religious until it was almost a mania. We were going to church every week along with two hours of formal prayers every night.

I wasn’t happy with all this. At fourteen I’d already been going to church school for six years but everyone I knew there was either in a gang or had gotten pregnant – normal for teenagers in the hood. The church hadn’t done them any good, not the kids anyway. My sister even ran with a gang and wore baggy clothes, but even though I just went skateboarding, they took it out on me. I got the shit kicked out of me all the time.

The best-case scenario was a broom, because I knew a broomhandle could break; but often it was an extension cord or a metal pipe. I thought of it as discipline: it took me a long time to realize it was violence, but that’s how Vietnamese parents did it.

Mom was the more violent of the two. Dad would only use his fists but she would hit me with things, terrorize me, smack me awake in the morning. Her voice scared the shit out of me. Back in Vietnam she had stepped on a landmine and lost a foot. It was when she was pregnant with my older sister. She was working on the farm in Phan Thiet taking care of the kids while my dad was in a forced-labor camp. This was some years after the war had ended – with our family on the losing side – and there were still plenty of live mines around.

It was touch-and-go after the mine exploded. She was tended by a North Vietnamese army medic and somehow, despite having no antibiotics or anaesthesia, both she and my sister survived. To this day she can’t talk about it but it must have changed her. I’m not sure if that trauma contributed to her anger and violence – but how could it not? She was already pretty mad: besides incarcerating her husband, the new government took most of the produce away, coming by every week to grab what they could. By the time I really knew her she was very violent, at least with me.

Eventually, as a junior in high school, I started sneaking out the window every night to spend time with my college-age girlfriend and rarely went home. I’d hang out with her or at my friend Steve’s house. His mom took care of gang members and runaways and strays of all kinds so I crashed there a lot. My grades took a beating. I went from a top student to Cs, Ds, and Fs.

My dad called the cops one day. I was in the car outside the whole time and when the cop took me to the door dad wouldn’t let me in.

Finally one of my boyhood friends gave me a job at a local computer store. It was an IT job and I soon saw that most of the staff were stealing parts. They were all doing it, so I did too, but of course I was caught and went to jail for the night. When my dad came to get me the cops had to kick him out of the police station he cussed me out so bad.

The whole religious thing was odd. They were hyper-religious but they owned a liquor store. They prayed all night but they cursed me and beat me. That all seemed to fit into their idea of what religion was. As for me, I never liked being forced to do things, and church was so boring. It didn’t mean anything.

Eventually, it was time to leave home a second time. There was a huge argument during my senior year. I sneaked in through the window one night and they caught me. I think, to my parents, it probably felt like nothing was working.

Go to church,” they demanded, “you’re going to hell if you don’t.”

“I’m out,” I said. “I don’t want to do that any more.”

“Then get the fuck out!” they screamed in Vietnamese. “We don’t need you here.”

So I left. I slept in the beat-up old truck my dad had given me. Then I became one of the strays Steve’s mom took in and I spent a lot of the next couple of years there.

I didn’t see my family again for several years. My younger siblings stayed in touch but I didn’t see my folks. They tried to reconcile and came to the school several times for meetings. One of their friends acted as mediator but I was stubborn.

“No, I’m not doing it,” I said. I didn’t want to go back. It was the mentality of, “I don’t need you guys. I’ll make it without you.”

I was in the database as a runaway and they had child services follow me. If they’d caught me they might have put me in foster care or something. But halfway through my senior year I was invited to a barbecue and when it was over I started washing the dishes. My hostess’s mother asked me why I was doing that and I said, “at home, if I don’t wash the dishes, I get in trouble.”

She offered me a room in the back of her house. I eventually agreed and started living there. This was a middle-class Jewish family that unofficially adopted me. They only had two rules: be home for the sabbath on Friday and don’t bring pork into the house.

At the time I was kicked out I was running on pure adrenaline. I thought I wouldn’t survive past 21 anyway. I was skateboarding and staying at various friends’ homes, living day to day. I felt like you only live once. Nothing matters because there’s no future.

“Hey, you want to go do this?” someone would ask.

“Yeah, sure, why not?”

“You want to go do that?” another would say.

“Sure, let’s do it.”

Like I wasn’t going anywhere. I thought I’d never do anything with my life.

Even after I got into the other family’s house, I felt uncomfortable living under someone else’s roof. I couldn’t wait to get out of there. Besides, I was the only Asian in a huge extended Jewish family and it wasn’t clear who did and who didn’t accept me. My Jewish mom told me “hey, you’re part of the family.” But she was the only one telling me that.

I’ve since been in contact with my Vietnamese family. My parents and I talk once in a while. Some members of my Jewish family talk to me now and then. But it’s been many years since I remember feeling like I had any family at all.

your road needs more sidetrips to solace: pleasure yourself with good food & friends that feed your soul.