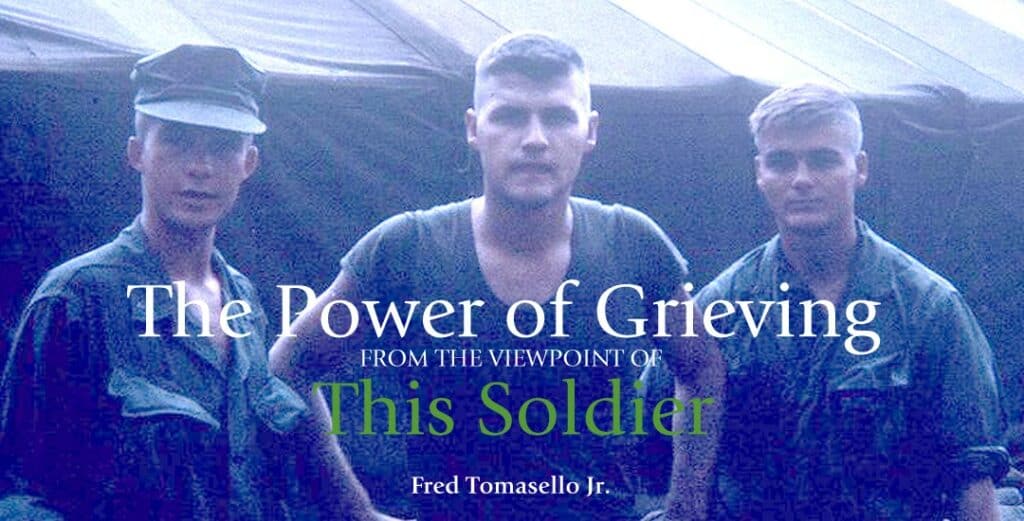

Fred Tomasello Jr. Guest Contributor

My main goal in life was to be a man, to prove myself. Machismo.

In our neighborhood, getting one’s ass kicked was noble. Running away was chickenshit.

The best way to reek of machismo, I decided, was to join the Marines and go to war.

“Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil because I’m the meanest mother in the valley.”

I’d experienced grief as a child. Dad bought me an ice cream cone. I begged for two scoops. He gave in. On my first lick, the top scoop rolled right off and splattered into the sand. I started to cry, to grieve my loss.

“Shut up, you little shit!” my dad yelled. “THAT’S why I wanted you to have just one scoop!” Reaching for his belt buckle, he added, “Keep crying, damn you, and I’ll give you a good reason to cry!”

So I shut up. Swallowed my grief.

My puppy got sick. Dad grabbed a burlap sack, a shovel, jerked up the dog and took it for a ride in the car. When he got home, he said, “The dog died. I had to bury it.”

Ashamed, I ran to my room so no one would see me cry.

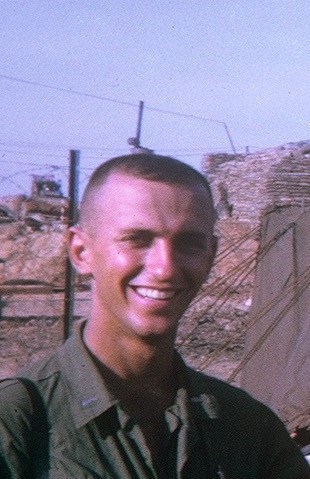

I volunteered for Vietnam. I’d made it through boot camp, Officer Candidate School, six months of Basic School and got my first choice of military occupational specialty: Infantry Platoon Commander.

My wife, who had just given birth to our first child, thought I was crazy and started to cry.

“Shut up, damn you!” I yelled. “Suck it up! Swallow those tears!”

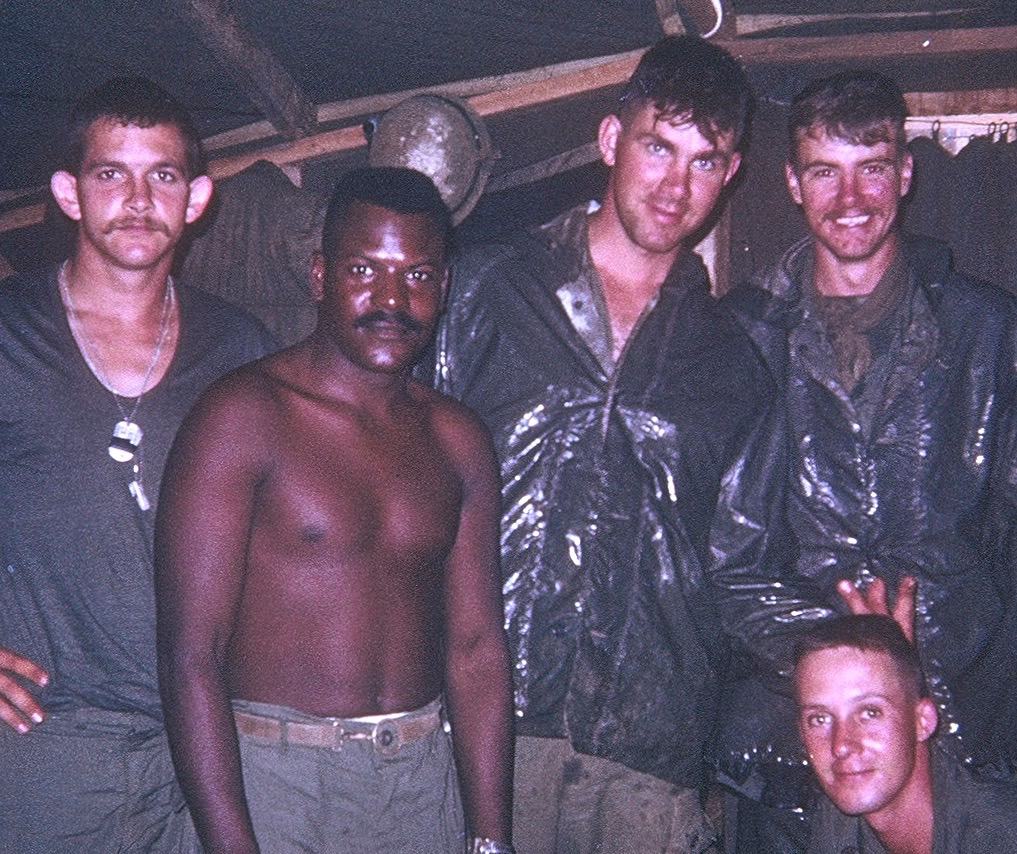

In a combat zone, the rule was, “Don’t get close to anyone. They could die any minute.” So I tried not to. About five months later, everyone in my platoon had been wounded, including me, and I had one man killed. Compared to other marines in other platoons, I was doing a good job. No one was crying or grieving. We were angry but happy to be alive. We’d handled dead and wounded Marines and enemy and civilian bodies, including women and children. We picked up people so mangled, tangled and maimed that we had to literally count heads to get a body count.

No grieving. No crying. No problem. Machismo.

I did cry one day but nobody saw me.

It was my first day up as an Aerial Observer, sitting in the back seat of a piper cub flown by a Marine. He called in a close air strike while I talked to the grunts on the ground. By some crazy error, an F-4 Phantom jet dropped four 250-pound bombs on top of a group of Marines.

“Turn that shit off!” they screamed over the radio. I burst into tears at the horror I saw and the realization of what we’d just done. We flew to Khe Sanh because a General directed us to explain what happened to his troops. No crying in front of him. I sucked it up. Machismo.

Back in the states, I went on casualty calls notifying families of Marines killed and wounded in action. Grieving wives, mothers, fathers and family members cried. I sucked it up. Swallowed my grief. On the way home, a six-pack of beer helped me sleep on a tear-soaked pillow.

I raised my three kids the same way my dad raised me. Tough. Machismo.

Anger was my substitute for grief. Rage ruined my marriage.

After leaving my family, I finally got some VA counseling. I had never spoken about my experiences because I would cry, and crying was chickenshit, so I shut up and swallowed my grief.

Writing my pain helped me put the hurt into words. The careful, most accurate selection of those words alleviated my pain. I slowly learned how to grieve.

None of my three kids or my nine grandkids called me this Father’s Day. They never have and probably never will. Machismo. They learned my lessons well.

I’ve been married to my second wife for 34 years. I still cry once in a while, sometimes in public. When I do and people stare, I touch my tears and tell them, “It’s a side effect of Post Traumatic Stress.”

We’re all learning better ways to cope, better ways to grieve when we hurt.

Grieving melts my anger into tears that stream down my cheeks. I patiently wait until the anger subsides. When it does, I rejoin my friends, and we can all share the full range of emotions that life offers us as human beings.

That’s the gift and the power of grieving.

Thank you for this opportnity.

As a viet nam vet, 2 marriages – divorced, and seriously Blacking this all out has been a serious problem. Anger started, stayed, till I started to cry, shedding tears of grief, from loss & pain.

This was recent, in last 2 + years, I’ve been going to the VA Hosp in Palo Alto, CA near where my oldest daughter, Alicia lives & I have to thank her so much. Grieving – anger = patience (crying)!!!