Craig Jones

Columnist

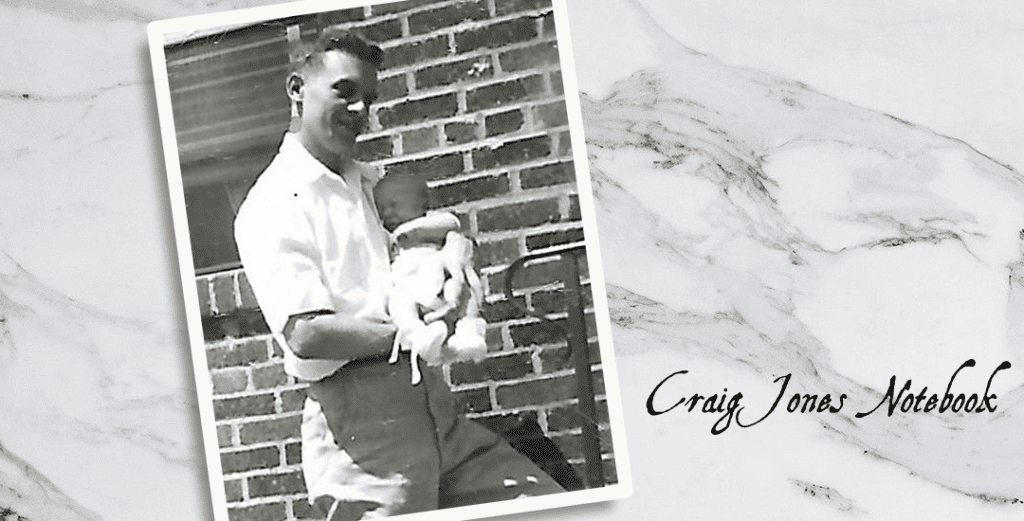

My dad died when I was five, in 1959. Lung cancer, non-smoker, who knows why, one chance in a million or billion (I don’t know) lung cancer, when he was younger than either of my sons are now. Any thoughts I have ever had about legacy and any thoughts I will ever have about his particular legacy, begin with the moment when he whispered his last breath in my mom’s ear.

In thinking about his death and his legacy, I was driven to look for a useful definition. One said “anything handed down by an ancestor or predecessor.”

Anything?

How about the contrail left feathering out behind a 747? The slick slime after a slug? The tomatoes that will be overflowing in our late summer garden? Are they not legacies of seeds? How about the cars being hauled out of the Merrimack River these days, as part of a massive cleanup? Legacies of insurance fraud, it looks like. How about the skunk scat in our backyard? How about child abuse?

There are all kinds of legacies, some that could be called positive assets in the whole life ledger, some rather less so. Legacies of DNA, legacies of philosophy, and legacies of childhood faith practice that have dyed one’s soul are more examples.

There’s the legacy of loss, as well, like the too-early death of a father. Throughout my boyhood I assumed I was the only one who had experienced this. I was the only kid I knew (other than my younger brother) who had to write “Deceased” on forms about parents at school and whose dad could not come to scout meetings and sports because he was not on the planet anywhere.

Of course, as I got older, I learned that many of us have experienced such loss, and that I wasn’t unique. Indeed, even Shakespeare addressed this, centuries ago.

He has the murderous King saying to his nephew Hamlet —

‘Tis sweet and commendable in your nature, Hamlet,

To give these mourning duties to your father;

But, you must know, your father lost a father;

That father lost, lost his; and the survivor bound,

In filial obligation, for some term

To do obsequious sorrow: but to persevere

In obstinate condolement is a course

Of impious stubbornness; ’tis unmanly grief

That’s not unlike saying to a man today “c’mon, sack up, shit happens.” True enough, that, but it sure feels like this particular death left its own particular legacy. Was it a big zero? Did he leave a big nothing in his wake? Did I fall into a big ditch of air and just keep falling?

Sometimes nothing is enough, though. George Kennedy’s character Dragline in “Cool Hand Luke,” says, after Paul Newman’s Luke won his poker game by bluffing —

“Nothin’ A handful of nothin’ You stupid mullet head. He beat you with nothin’. Just like today when he kept comin’ back at me with nothin’”. (Referring to their boxing match.)

Luke says —“Yeah, well, sometimes nothin’ can be a real cool hand.”

What could be the legacy of nothing, of a missing person? Did I get a real cool hand? The philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre thought so, losing his own father when he himself was a young boy.

“The death of Jean Baptiste,” Sartre opined, “was the big event of my life. It sent my mother back to her chains and gave me my freedom. There is no good father, that’s the rule. Don’t lay the blame on men but on the bond of paternity, which is rotten… Had my father lived, he would have lain on me at full length and would have crushed me. As luck had it, he died young.”

I don’t share Sartre’s exhilaration about the loss of my own father, but he was right about one thing. It was the big event of my life, most certainly, the one with the longest shadow.

His death did give me years with my maternal grandfather, George Leighton, who became very much like a father to me, and I’m grateful for his memory. My younger brother and my mom and I moved to Maine after my dad’s death, and we lived in the upstairs apartment of the house he built. It was a place of refuge, a querencia, at a really scary time, and it was there I lived until heading west to college and adult life.

He died in 1985, one month shy of 101 and remains the only centenarian I have known personally. He was a classic Downeaster (Downeastah, rather) who, among much else, taught me gardening, fishing, nail-banging and a general sense of conservation of resources. I still feel compelled to turn off unnecessary lights, for example, though I don’t go as far as putting unused already-toasted bread back with the rest of the loaf, which I saw him do. That’s probably because there’s never any leftover toast, in our house, come to think of it.

I didn’t know enough about gratitude to have told him how much he mattered to me before he died. Maybe he knew, but there is a lot I could have said that I just didn’t say or didn’t know how to say.

What’s helped me with this is the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. He was emperor of Rome from 161 to 180 and also managed to write a kick-ass philosophical treatise that has endured from antiquity. He’s a model of gratitude for me because he begins with several pages acknowledging people in his life for what they gave him. Gratitude first, everything else to follow, that’s the way to live, in my book.

The first entry in his Meditations is “From my grandfather (Verus) I learned good morals and the government of my temper.” The second line is “From the reputation and remembrance of my father, modesty and a manly character.”That struck me afresh with a recent rereading as I realized all I had of my own father is reputation and remembrance.

I have known and loved this section for many years, but what I did not know until more recently that Marcus Aurelius was adopted by his grandfather after his own father’s death. My grandfather didn’t technically adopt my brother and me, but I find some resonance there, through the centuries, and I’m grateful that I got to spend my boyhood with such a great man.

There’s no replacing a father but, as Dr Robert Holden said, “The miracle of gratitude is that it shifts your perception to such an extent that it changes the world you see.”

A story in the fairy tale Through the Mickle Woods speaks to this miracle.

In a kingdom long ago there was a man who lived alone. In spring he never sowed his seeds for fear there might be drought, and in fall he would not travel lest his ship be blown into the deep. But though he locked his doors inside and out, it did not bring him peace.

One day a bird, small and slight as a pebble, flew to his window. He marveled at her green wings and at the beauty of her song.

“I have heard that wind can uproot a tree from the ground,” said the man. “Are you not afraid of wind?”

The bird cocked her head brightly. “Of course,” she said.

“And I have heard that fire can sweep a forest in a day,” the man said. “Are you not afraid of fire?” “Yes,” she said. Her wings, thin as pages in a book, glinted in the yellow sunlight.

“But if you are afraid,” asked the man, “why do you fly? Why do you build your nest?”

The bird cracked a grain of millet in her beak. “There are things I would not miss,” she said. “Every day there is morning, ripe as a peach.” She trilled a score of grace-notes effortlessly. “And fledglings in the spring, of course – small things.”

“I do not wish to hear of these,” said the man. “What of wind and fire?” The bird considered thoughtfully. “My song,” she said finally, “requires them all.” The man watched her fly away, as frail and strong as ashes dancing in the air.

The loss of my father, the empty hole, impossible to fill, was necessary for my particular song, it appears.

Brilliant!

Your writing voice is authentic, genuine and vulnerable.

I am moved and touched and will dwell on your piece as I look again at my own father’s sudden death when I was 28 and he 48.

Kind regards,

The depth of your gift was received in small shovels full of poignant imagery.

Each little word mound was a sub-lesson.

It is clear your father smiles down on a rich legacy and he knows that

his best was quite good, after all.